Falls Church’s Black History: A Welcoming Community That Has Not Always Been So Welcoming

By Edwin B. Henderson II

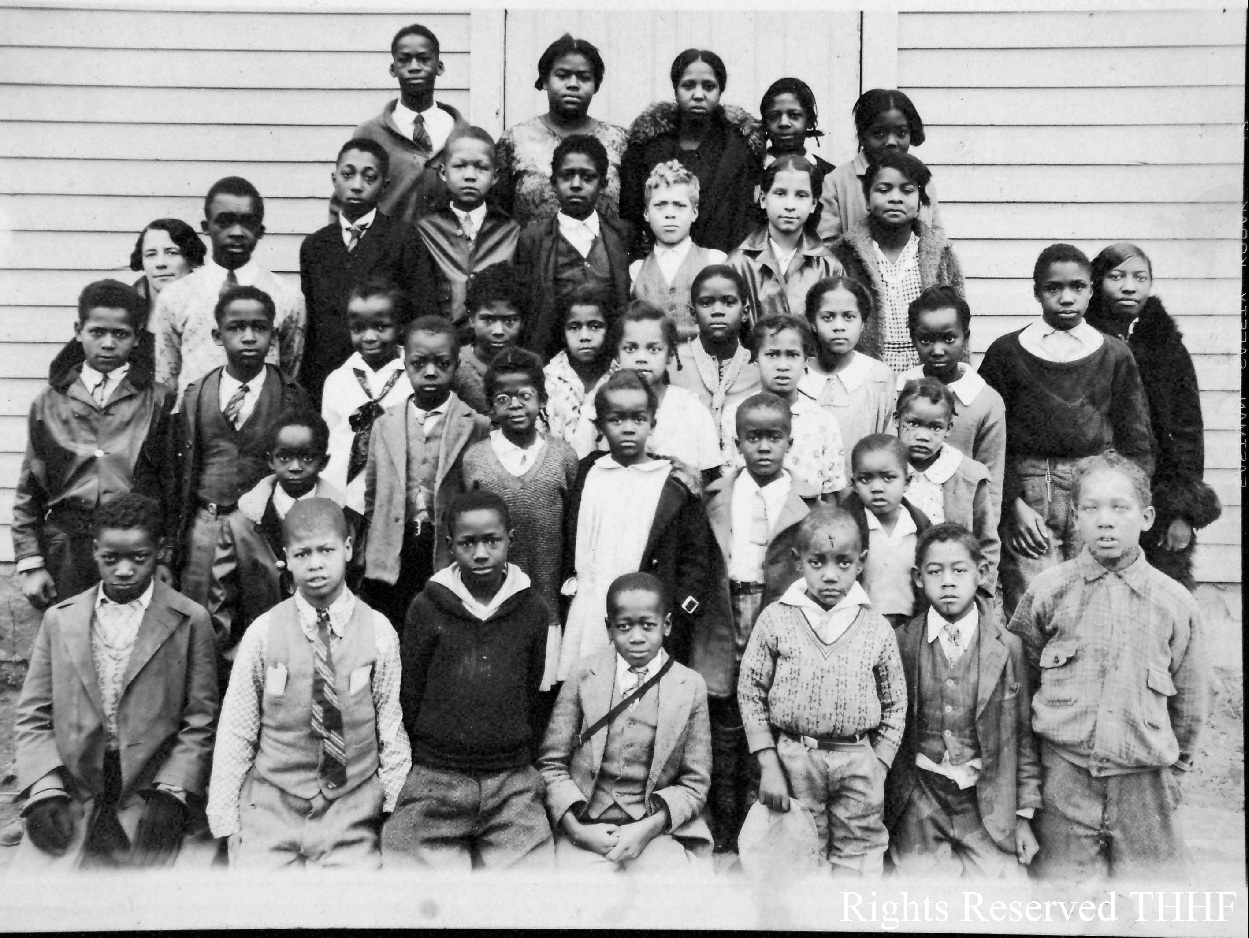

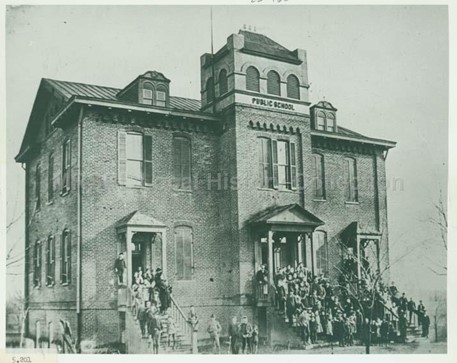

Picture above of Mary Ellen “Miss Nellie” Henderson with her students at the Falls Church Colored School

Black History honored at Tinner Hill

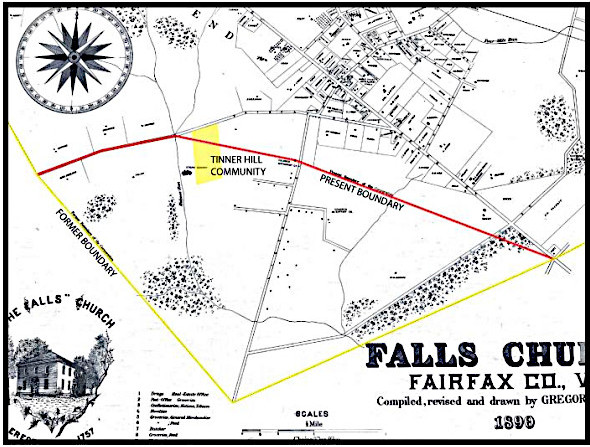

On January 16, 2024, the Falls Church City Council proposed an amendment to the City’s Comprehensive Plan that would officially make a core area of Falls Church “The Tinner Hill Historic and Cultural District.” This area, centered along South Washington Street (Lee Highway), will include the Tinner Hill Civil Rights Monument, Galloway United Methodist Church, the Henderson House, and the Tinner Hill Historic Site, as well as the homes in the Tinner Hill community along Tinner Hill Road.

The initial memorandum asking for this special designation was sent to the City Council on April 17, 2023 by the Falls Church Historical Commission on which I serve as vice chair. Officially designating the Tinner Hill Historic and Cultural District is honorific and does not affect zoning, permitting, or taxation, but hopefully will encourage heritage tourism and foot traffic to the area. Who knew it would be so difficult? But, I guess the wheels of bureaucracy grind slowly.

Those of us who live in Falls Church like to think that we are a “welcoming community,” but it wasn’t always that way. For some, the City’s history is a difficult one. But for those who fought, struggled, and succeeded, the story is a triumphant, victorious one.

Civil War and murder

In the early years of the Civil War, a school for African Americans was started by a lay preacher named John Read. His daughter Betsy began to teach Black people to read and write, which was against the law in Virginia. The school had room for 30 students, but as many as 60 would show up. So, 30 would sit, while 30 stood. After a while, they would change places.

Soon people hostile to the school began to take notice. Betsy then went to the homes of her students to teach much smaller groups. It was still a dangerous endeavor. Finally in 1864, John S. Mosby’s Rangers came into the town under disguise and kidnapped Read. Frank Brooks, a Black home guard in the town blew his trumpet to sound the alarm of Mosby’s approach. Brooks was shot and killed as the Rangers proceeded to their destination where they captured Read and another home guardsman named Jacob Jackson. They took the men out near Hunters Mill where they were both shot in the head, so the Rangers thought. Read died, but by some stroke of luck, Jackson escaped death, only losing an ear, and made it back to town to tell the whereabouts of Read’s remains.

Before the Emancipation Proclamation, the 1860 census indicates there were 250 enslaved people within the Village of Falls Church. Once Union troops occupied Falls Church, those held in bondage were freed, because Virginia was a “state currently in rebellion…” According to the 1870 census, the African American population in the village comprised 42% of the inhabitants.

Post-Civil War early emancipation

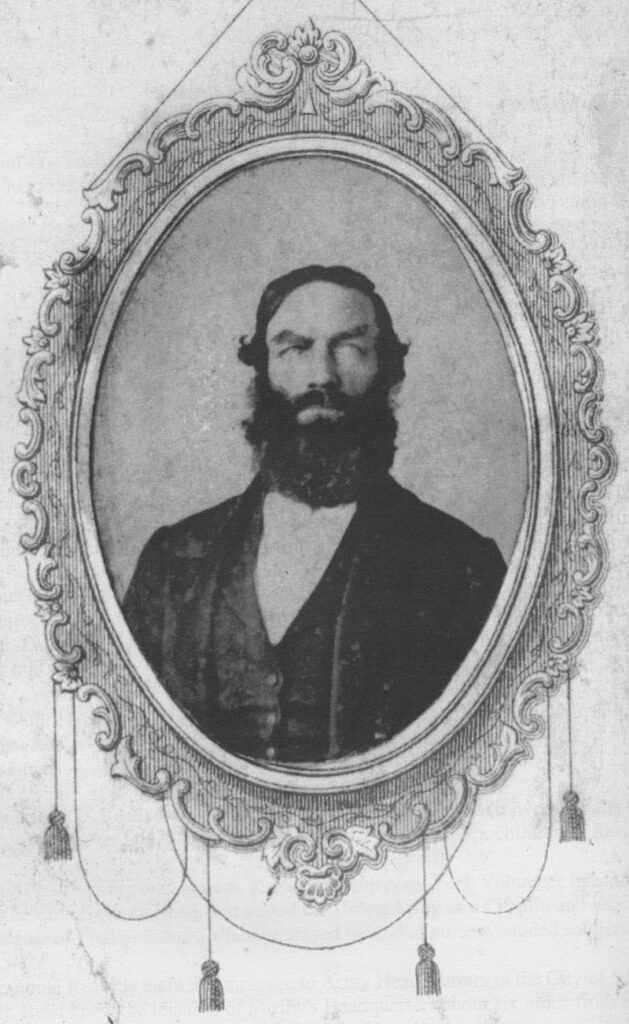

African Americans were able to purchase land in Falls Church, thanks to such liberal minded Northerners as Colonel John S. Crocker, a former Union officer. Many White Southerners were not willing to sell land to former enslaved people. Col. Crocker acted as a front man, buying the land and then selling it to African Americans.

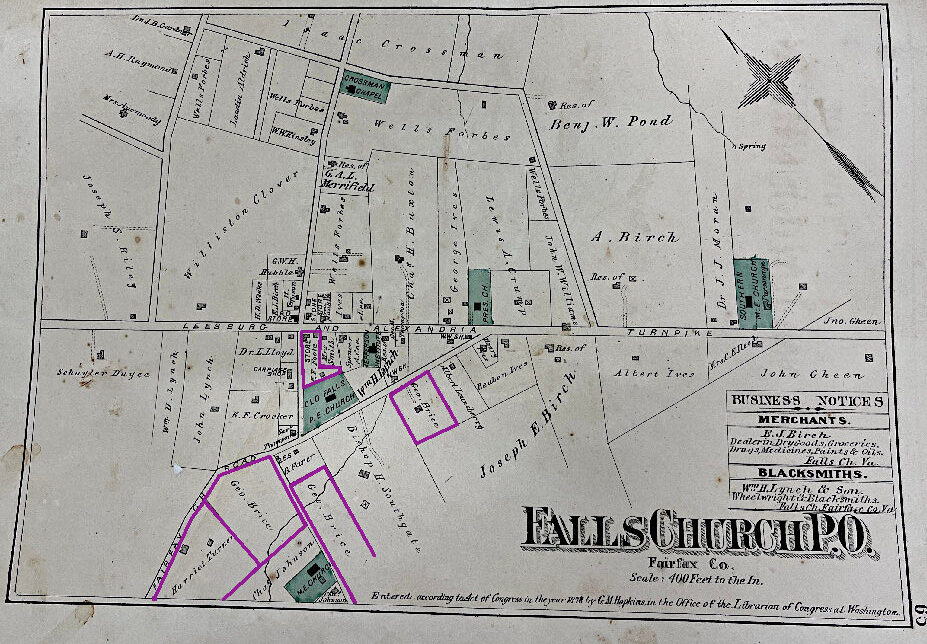

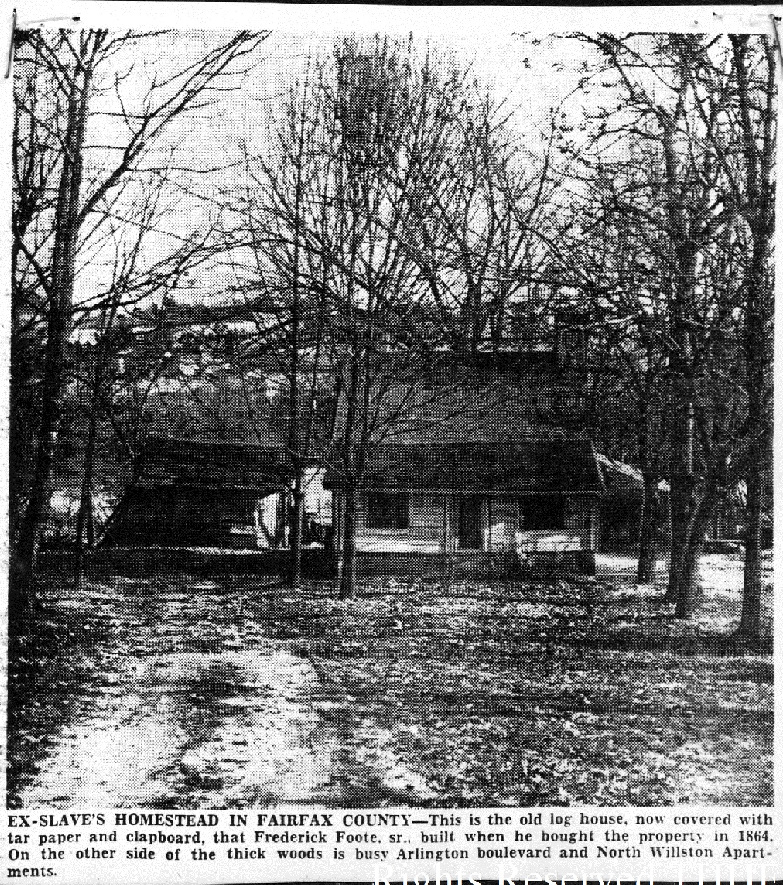

Early African American landowners included Frederick F. Foote and Harriet Brice, who purchased their properties before the end of the Civil War. Foote bought 28 acres of land from Daniel Miner, who had once owned him. Brice once boasted that she purchased a plot of land in the center of town. James Lee acquired a relatively large plot from Col. Crocker along Shreve Road (now Annandale Road). Others were also able to buy lots in the area that was once the Dulaney Plantation. Soon, a significant number of formerly enslaved people lived on the southern border of the village.

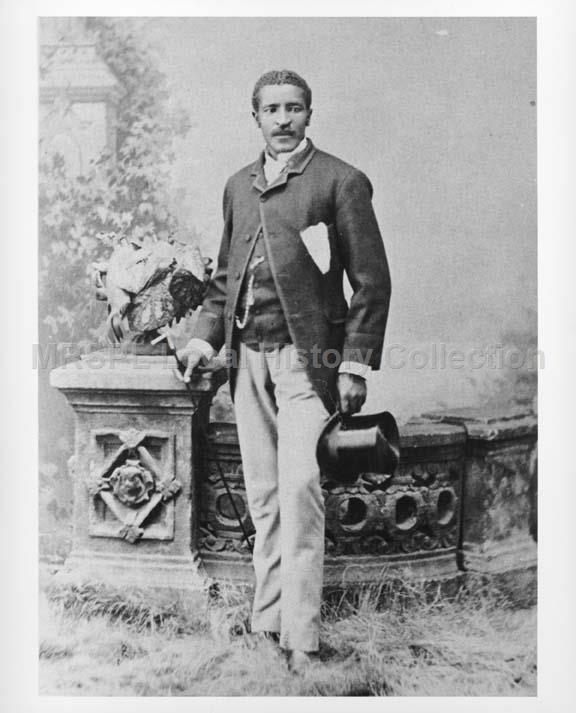

In 1875 when the village became a town, African American cobbler and general store owner Frederick F. Foote, Jr. was elected Town Constable. In 1880, he was elected the first African American Town Councilman. Foote’s electoral success was largely due to the fact that everyone knew him since his store was the largest in the area. People bought their goods from him at the store located in the center of town, next to The Falls Church. But another reason for his electoral success was the large male African American population in Falls Church that was able to vote. The majority of African Americans voted Republican, the party of Abraham Lincoln.

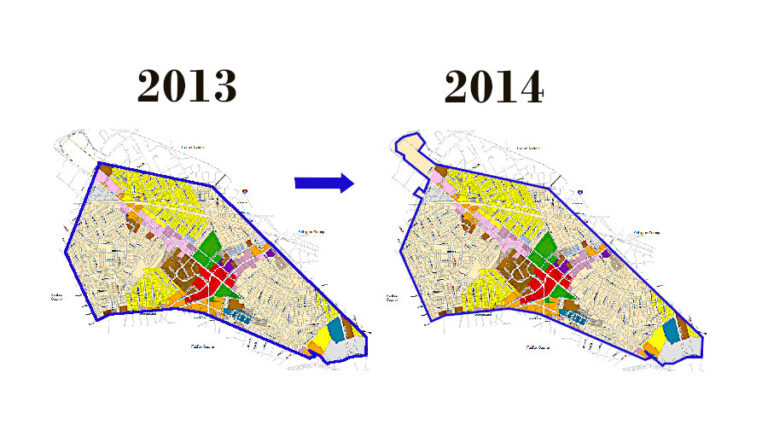

Gerrymander and retrocession

Foote’s election was problematic in a small southern town where most Whites voted the Democratic ticket. His tenure as a Town Councilman was filled with contention and bitterness. The majority of the Town Council members were Democrats, and the 1890s were an era of retribution by Southerners who had been displaced by African Americans during Reconstruction because of their stance during the Civil War. This was a dangerous time for African Americans who had made great strides during the 10-15 years following the end of war.

Fred Foote found himself in a hostile environment of constant marginalization at every turn during his time on the Council. In 1887, the final step was taken when the majority of the Town Council voted to gerrymander out of the town the section where most of the African American population lived. One third of Falls Church was retroceded back to Fairfax County, which effectively meant that African Americans had no say in town matters. Additionally, their once strong block of votes was marginalized because African Americans were now a small portion of the much larger jurisdiction of Fairfax County. Foote didn’t live long enough to see the end of this process, passing one year before it was finalized by the state legislature in Richmond.

Schools: Separate and unequal

One bright spot occurred in 1888 when the Society of Friends (Quakers) built the Falls Church Colored School with support from the Providence District of Fairfax County. Land was donated by James Lee, and a two-room schoolhouse was erected. The school was just a building without running water and with outhouses for toilets and a pot belly stove in the middle of the building that provided the classes heat in winter.

It was very different from the Jefferson Institute, the school for Whites in Falls Church, built in 1882. This school was a two-story brick structure with six classrooms, indoor plumbing, and central heat. When the White students received new textbooks, the old textbooks were passed down to the Black students. The books had missing pages and expletives written by the White students, who knew their old books would end up in the hands of African Americans.

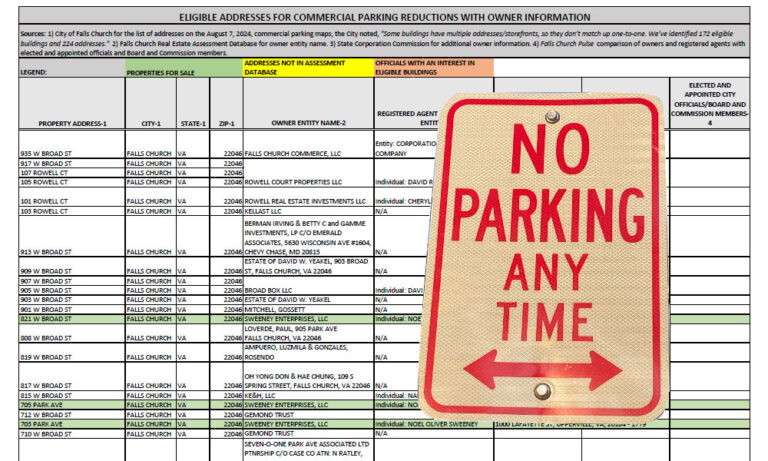

Falls Church passes a segregation ordinance

In 1915, the movie Birth of a Nation produced a surge in membership of the Ku Klux Klan across the country. Here in Falls Church, we had our own rise in racial tensions with the proposal of a segregation ordinance designed to relegate Black people to a small section of town. Not only about segregated housing, this ordinance also effectively dictated where Black people could own land. The areas that were designated for Whites only basically meant they were “Sun Down” areas. In other words, you better not be caught in them after sundown if you were Black. The area designated for “Colored Only” constituted just five percent of the town’s land mass.

CCPL and NAACP

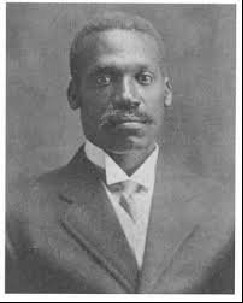

On January 8, 1915, Edwin B. (E. B.) Henderson called a meeting of nine men who were considered the pillars of the Black community in Falls Church, which was held at the home of Joseph Tinner, a stone mason, known for his adeptness as a public speaker. These gentlemen formed an organization called the Colored Citizens Protective League (CCPL). They opposed restrictions on the African American population and started a letter writing campaign, sending letters to all the Town Councilmen as well as local churches and businesses, asking where they stood on the proposed segregation ordinance.

In addition, the CCPL wrote to Dr. W. E. B. DuBois, asking for help from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) , and permission to form a branch of the Association in Falls Church. (Unfortunately, the bylaws of the NAACP required that in order to form a branch, 50 signatures were necessary. For a small farming community in a Southern state, that was a dangerous proposition). Henderson appeared before the Town Council and pleaded with its members not to approve the segregation ordinance, but the measure passed. That summer, a referendum was put before the town on the issue of creating the segregation districts. It, too, passed.

The CCPL then brought a lawsuit against Falls Church in Fairfax Circuit Court, an action that effectively placed an injunction on the enforcement of the ordinance. Henderson invited the judge to observe the districts that were proposed, after which the judge decided he would not rule on the matter because there was a similar case scheduled to come before the US Supreme Court. In 1917, Warley v. Buchannan was heard in the Supreme Court, which ruled that creating such ordinances was unconstitutional, thereby nullifying the ordinance in Falls Church.

Lee Highway

The US Supreme Court ruling was a clear victory for the CCPL. But it wouldn’t last. The CCPL did become a branch of the NAACP, and there was much activism throughout Northern Virginia, starting with the formation of branches in Leesburg, Arlington, and Alexandria. But with the 50th anniversary of the Civil War, the call for Confederate monuments and a highway to honor Robert E. Lee put a damper on this progressive activism. There was talk of a Robert E. Lee Highway stretching from one end of the country to the other, from the East to the West. It might not have been as popular in other localities, but here in Lee’s Virginia, and particularly in Arlington, Falls Church, and Fairfax County, the message was loud and clear.

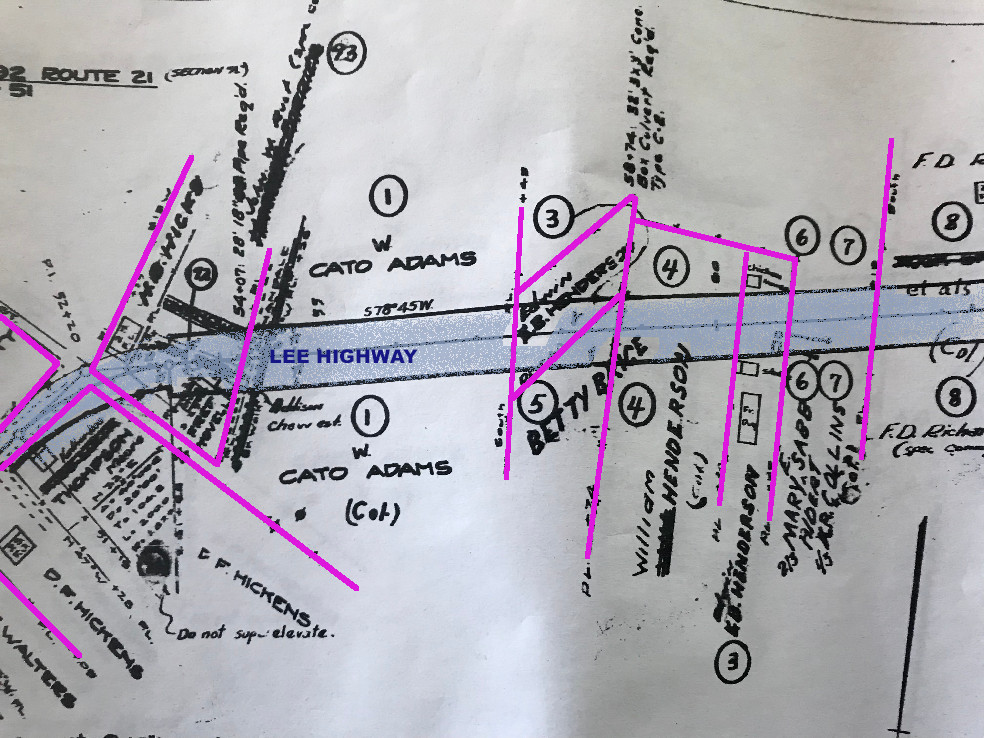

There were mass meetings of concerned African Americans. James Weldon Johnson, the field agent for the NAACP, came and spoke. But little deference was given to the concerns of Black people during this era in America. In 1922, the route once known as Fairfax Court House Road, which stretched from Leesburg Pike, past The Falls Church, the Rolling Road, and what is now South Maple Avenue, was renamed Lee Highway. Lee was made a US highway, Route 29. The road cut directly through land that was owned by African Americans, the land taken for it by eminent domain.

Our schools, our shame

The Falls Church Colored School was shuttered during World War I due to the lack of teachers. After the war, Mary Ellen “Miss Nellie” Henderson was approached to reopen the school. She was married to E. B. Henderson, whose family traced its roots in Falls Church to before the Revolutionary War. The Hendersons were both teachers in Washington, DC; however, back then when a woman married, she was no longer able (or allowed) to teach in the nation’s capital. At first Mary Ellen resisted the request, saying she had just had a baby, but the community promised to help care for the child. The school reopened in1919, and Miss Nellie remained its principal for the next 30 years.

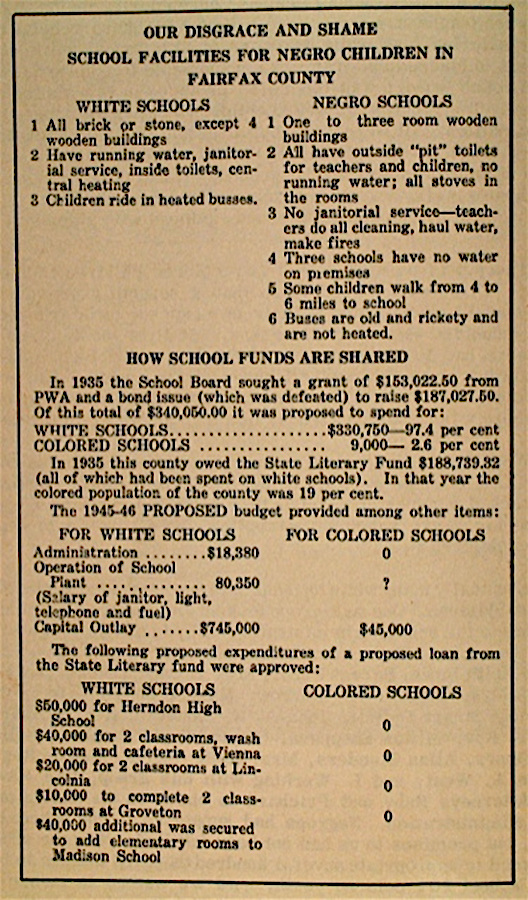

A model teacher in Washington, DC, Mrs. Henderson’s standards were high. She approached the Fairfax County School Board on many occasions about the deplorable conditions under which she taught at the Falls Church Colored School. Finally in 1938, she used the Fairfax County Public Schools’ budget to disprove the faulty logic of Plessy v. Ferguson’s “separate, but equal” clause. In a study titled “Our Disgrace and Shame,” Mrs. Henderson showed how for that year, only 2.6% of the school budget was allocated to educating Black students, while 97.4% of the funding went to the schools educating White students.

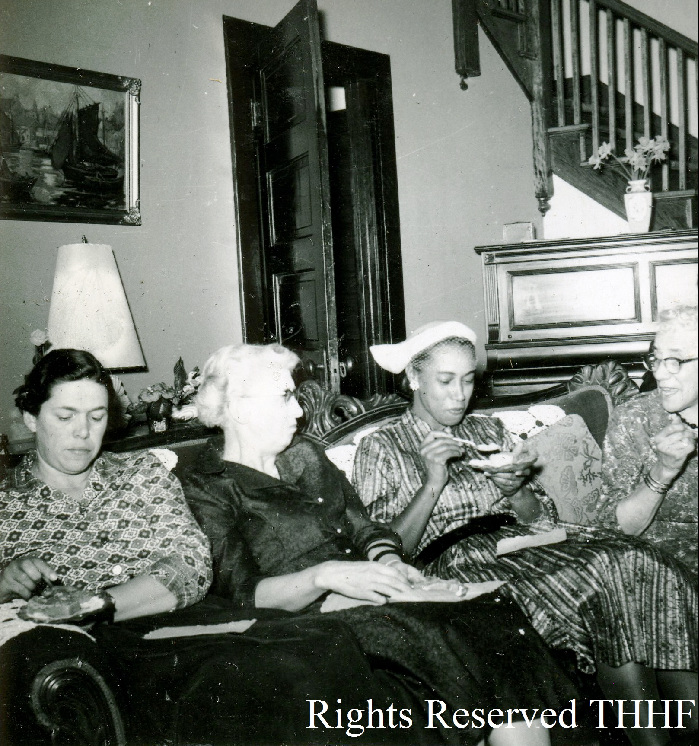

Armed with this information, she formed an interracial committee to advocate for better schools for African Americans. Her efforts led to the replacement of the old, dilapidated Falls Church Colored School and the building of the James Lee Elementary School, the first modern school for African Americans in Fairfax County Public Schools.

A vibrant Black community in Falls Church

The center of town in Falls Church was always a mix of Black and White, old and new. Fred Foote’s store next to The Falls Church Episcopal Church was bought by his cousin Eliza Henderson, who passed it down to her daughter-in-law, who ran it for a third generation into the 1940s.

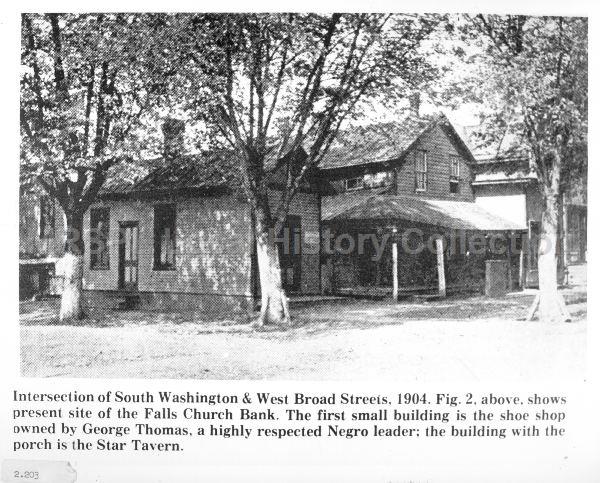

On the north side of Lee Highway stood the Falls Church Town Hall and jail and the town cobbler, Thomas’s Shoe shop, whose proprietor knew everyone’s shoe size and made shoes for both Black and White citizens. Robinson’s Barbershop was between the cobbler and the Falls Church Bank, helping make this area the center of commerce for the little town, which we now call The Little City.

Although strictly segregated, the African American community along Annandale Road was a vibrant community with two churches, Galloway United Methodist and Second Baptist Church. There were also social organizations such as the King Tyree Prince Hall Masonic Lodge, the Eastern Stars, the House of Ruth, and the Odd Fellows Lodge. Behind the Saunders’s home was the local watering hole, the Blossom Inn Beer Garden, which doubled as a convenience store during the day where children attending the Falls Church Colored School bought their candy.

Dr. Harold Johnson, a professor at Georgetown University Medical School, provided excellent medical care for this community. And first-rate dental care was offered by Dr. Montgomery, whose office was on Annandale Road. Although it might not seem much by today’s standards, at this time the African American community had all they needed to create a lively social structure for African Americans in Falls Church.

Starting around the 1890s, Merton E. Church sold lots to African Americans so they could build homes in the Southgate community. In the beginning, there were no public services there, including mail, trash, water, and the like. Viola Hudson, a dynamic woman, was the force in the community who would not accept second-class citizenship and led the charge to finally bring these basic services to that community.

Zoning and eminent domain

Eminent domain and zoning African Americans out of their property became a powerful tool in the government’s tool box to displace Black people in the early-to-mid-20th century. Whenever there was a need to build a road or something, “for the public good,” the first place considered was the path of least resistance. It has been a common theme throughout the United States — whenever a highway, or a school, or a hospital, or some facility that would serve the public good was needed, the cheapest land, the weak outcry from a marginalized population became easy pickings and a first resort for these projects.

Later after World War II, when large residential developments were starting to pop up everywhere in the Northern Virginia suburbs, the need for a shopping center or a new high school commonly resulted in encroaching on land previously owned by African Americans.

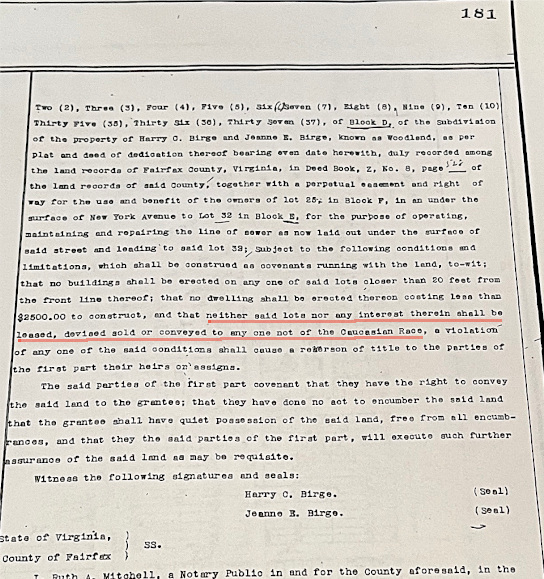

Red lining, a practice established by the Federal Housing Authority (FHA) and used by lenders and insurance companies, made it difficult, if not impossible, for Black people to qualify for FHA loans. And, in many of these new developments, the deeds had covenants that restricted the property from being sold to Black people. This era of massive development, between 1945 and 1970, meant buying a home and building middle class wealth for White families in the suburbs, but not for African Americans. Black families were locked out of the largest shift in wealth accumulation in America.

Integration: A double-edged sword

Integration, or desegregation, in Northern Virginia came slowly. The Harry Byrd Machine vowed to set up roadblocks to the US Supreme Court decision in Brown v. The Board of Education, invoking the “Massive Resistance” movement to block the integration of schools in Virginia. Ultimately, Falls Church City Public Schools (1961-62) acquiesced to the court ruling more quickly than did Fairfax County Public Schools (1965-66). Mr. John A. Johnson, Falls Church City School Board chair, met with both E. B. and Mary Ellen Henderson, regarding the issue, and was open to integration as early as 1955, but resistance from other members of the school board and pressure from Richmond kept the idea from taking hold and growing here in Falls Church City until the early 1960s.

When desegregation of the schools finally came to Fairfax County in 1965, the local James Lee Elementary School was completely shuttered. Three years later, a young Black youth running from the police along Annandale Road was killed by the police vehicle. Consternation among the residents of the community led to protests along Annandale Road. The protest were effective in pressuring the Fairfax County government to reconsider. The community needed something for the youth in the James Lee community, and the empty school was reopened as the James Lee Community Center.

The importance of knowing our history

Interest in this history was reinvigorated with the founding of the Tinner Hill Heritage Foundation, Inc, in 1997. The Foundation is responsible for building monuments, conducting oral histories, painting murals, constructing a heritage trail, and erecting historic markers in the area. The Foundation successfully encouraged the local school system to name its middle school for Mary Ellen Henderson, the principal of the Falls Church Colored School. The Foundation also hosts an annual music festival to entertain and help carry our message of community well being here in Falls Church.

Although Falls Church hasn’t always been a welcoming community to all its citizens, knowing and telling the truth of our history is important so that we are not doomed to repeat the mistakes and missteps of the past. My hope is that we move ahead to forge a more harmonious future for all citizens, regardless of our differences, whatever they are, whether they are based on race, nationality, religion, creed, or sexual orientation. In the words of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., “We will either learn to live together as brothers, or die together as fools.” I would prefer the former.

References

- 100 years of Black Falls Church, website containing historical photos, some are shown here, and documents.

- The Tinner Hill Heritage Foundation website

- The Grandfather of Black Basketball: The Life and Times of Dr. E. B. Henderson, Edwin Bancroft Henderson II, 2024, Rowman & Littlefield.

- The Story of Falls Church, 2019, City document containing historical photos.

- Atlas of Fifteen Miles Around Washington, including the Counties of Fairfax and Alexandria, Virginia, 1879, G.M. Hopkins, C.E., Philadelphia.

- Tinner Hill, Virginia: A Witness to Civil Rights, Anna Buczkowska, Basem Saah, and Paul Kelsch, July 30, 2011.

- Meeting John A. Johnson: Unsung Hero In Falls Church’s 1950s Struggle to Integrate Its Schools, September 25, 2005, Falls Church News Press.